Fatwatch

I said I'd build it. Last post I wrote, “That's the next build.” The Eat Watch on my wrist worked, but it was deaf. I logged meals in MyFatnessPal, then tapped the same calories into the watch by hand. I was the middleware. Two systems, no bridge, me in the middle pressing buttons.

Then I built DogWatch.

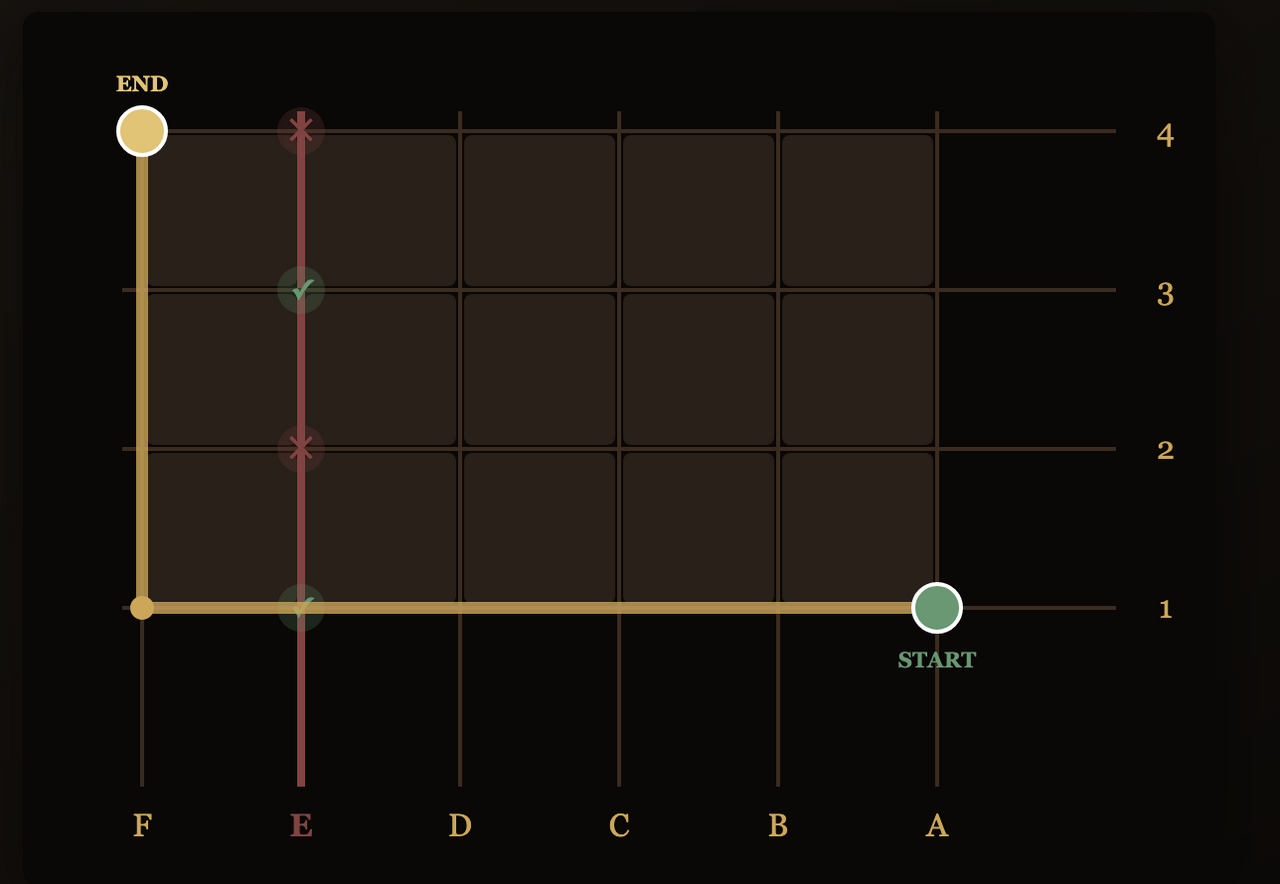

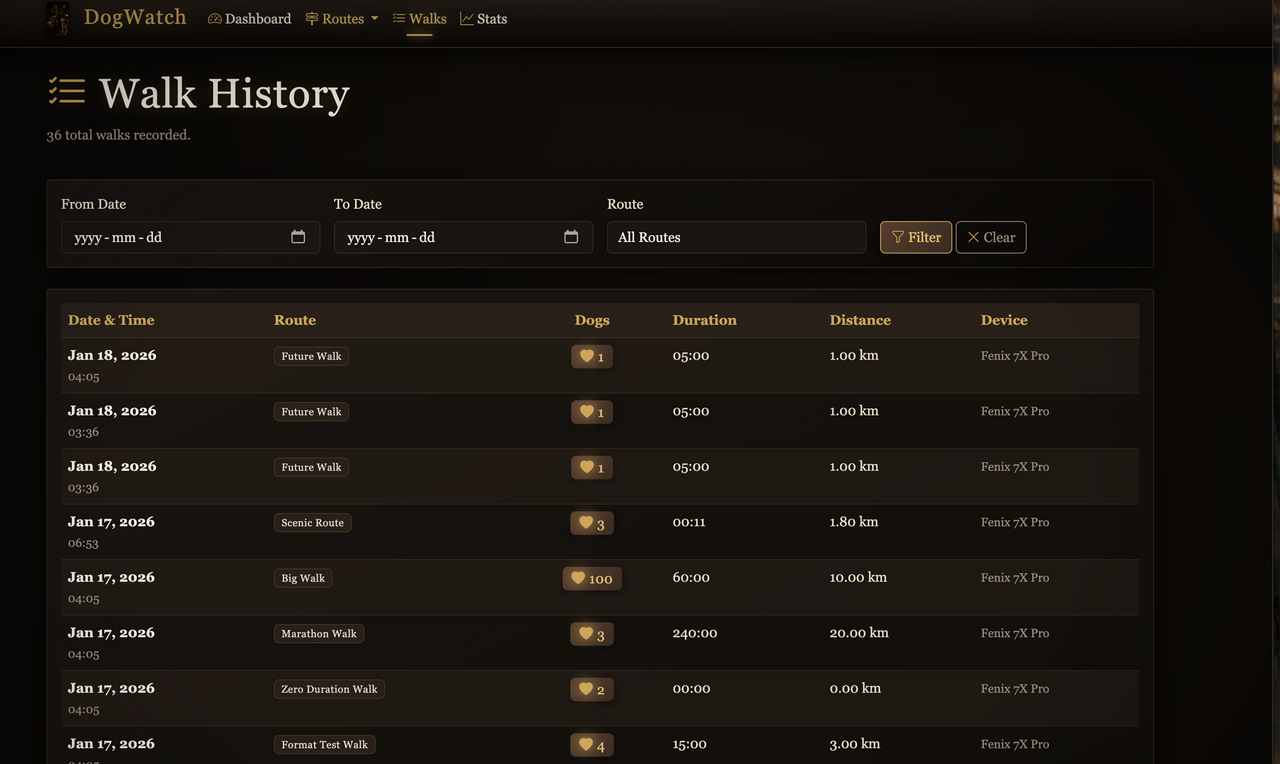

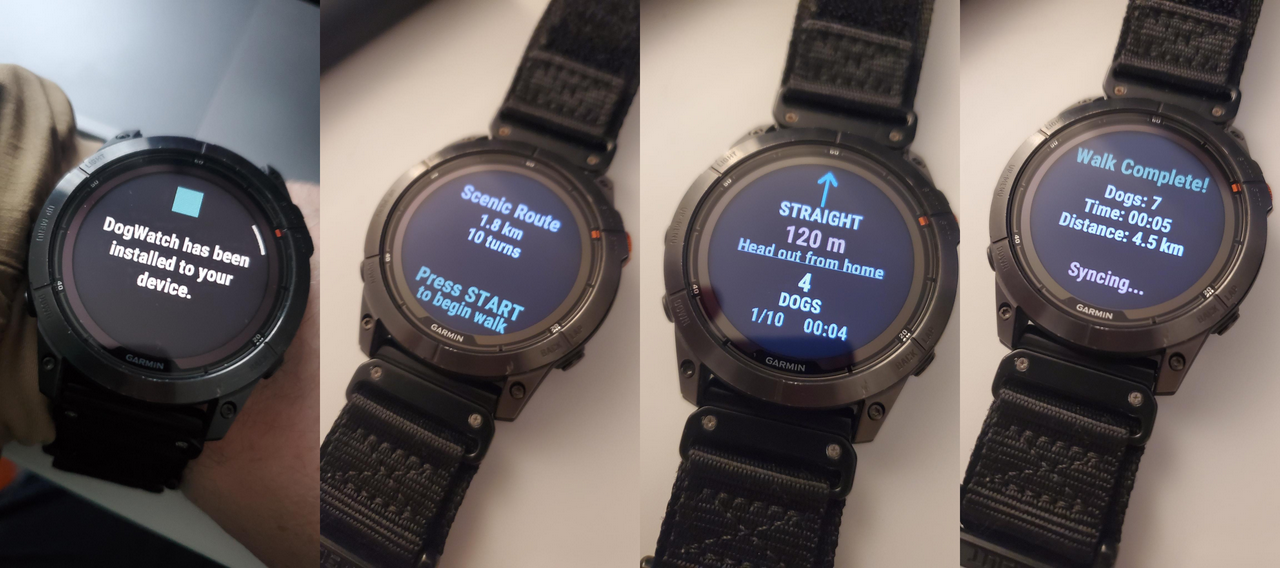

DogWatch was supposed to be about counting dogs on the walk to daycare. It was. But it taught me plumbing. Data flowing from wrist to phone to server. A Garmin app that talked to Django. By the time the first walk synced, zero dogs and all, I had a pipeline.

If I could sync dog counts, I could sync calories.

The Build

The architecture is simple because the watch is stupid. On purpose.

Every five minutes, the Garmin sends one request to the server: give me today's numbers. The server checks what I've logged in MyFatnessPal, does the maths, and sends back three numbers. Goal. Consumed. Remaining.

The watch stores nothing. Calculates nothing. Decides nothing. It asks one question and displays the answer. Green means eat. Red means stop.

When I log a burrito at lunch, the server knows within five minutes. I don't open anything. I glance at my wrist. The number moved.

Midnight comes, the count starts fresh, and the watch goes green again. The first morning it worked, I just stood there looking at it. A zero I hadn't typed.

Walker called it a fuel gauge. The gauge doesn't know how the engine works. It just reads the tank.

The Skin

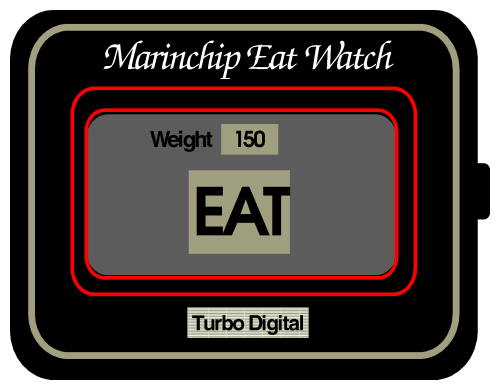

Walker never built the Eat Watch. But he drew one. In The Hacker's Diet he mocked up a watch face: square, black, a red-bordered LCD screen with “Marinchip Eat Watch” in italic script across the top. It looked like a Casio from 1985. A “Turbo Digital” badge sat at the bottom like a maker's mark on a thing that never existed.

I wanted mine to look like that. The problem was shape. Walker drew a rectangle. Garmin makes circles. So I redrew it: same bezels, same script, same badge, bent around a round face. The LCD tan, the red border, the italic branding. All of it, just curved.

Now it sits on my wrist. Green text, “EAT,” the remaining calories underneath. A relic from a future that never shipped, finally running on real hardware.

The Arc

A calorie counter. Then a Garmin app. Then a system to connect them. Each build was the logical next step, each question a little harder than the last. Could I build something useful? Could I build for hardware? Could I wire it all together?

The answer kept being yes.

The calorie counter talks to the watch. Loop closed.

I look at my wrist. Green. I can eat.

Walker imagined this in 1991. He never had the watch. I do.

-—

If you want to try this yourself:

FatWatch is a Garmin watch face that connects to MyFatnessPal. If there's enough interest I'll make both available. MyFatnessPal is the calorie counter that started all of this. You can read about it in the first post in this series.