Building a Garmin Eat Watch in Hours – Not Weeks

I’d just finished MyFatnessPal when I came across an old idea from The Hacker’s Diet: the “Eat Watch.” A traffic light for your appetite. Green means eat, red means stop. A few hours later, it wasn’t just an idea anymore — it was running on my Garmin fēnix 7X Pro.

Source concept: The Hacker’s Diet – “The Eat Watch” https://hackersdiet.org/hackdiet/e4/eatwatch.html

Original illustration (credit: John Walker / Fourmilab):

From Idea to Wrist

It started as a passing thought: Wouldn’t it be cool if someone built that? I had no experience with Garmin’s Connect IQ SDK or MonkeyC, their proprietary language. But I wanted to see if I could go from concept to working prototype in a single session — with help from AI.

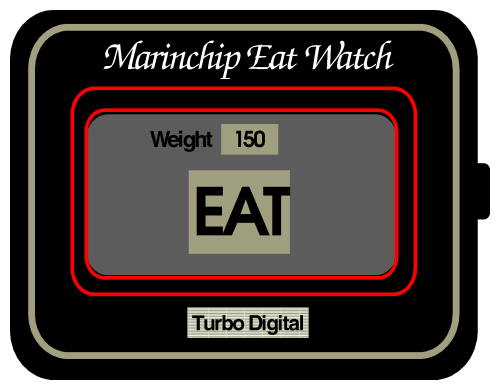

The concept was simple: a wrist-based calorie traffic light that shows EAT (green) or STOP (red) depending on your daily calorie budget.

Instead of telling AI to “build a calorie tracker,” I started with something broader:

Create a roadmap for a Garmin app that shows EAT/STOP status based on calories, with phases for MVP, UX improvements, and integration.

That single prompt gave me everything I needed:

- Development phases

- Clear success criteria

- Feature priorities

It turned a loose idea into a concrete plan.

My version (prototype on Garmin fēnix 7X Pro):

Phase 1: Laying the Groundwork

The hardest part wasn’t the logic — it was the structure. Garmin apps need specific manifests, signing keys, and resource folders. MonkeyC feels a bit like Java but has its own quirks.

Prompt that saved hours:

Set up a Garmin Connect IQ project for the fēnix 7X Pro with correct folders, manifest, and build process.

The AI generated:

- Complete manifest.xml

- Resource folder structure

- Build script with key generation

Then I hit a signing key error. One more prompt fixed it instantly:

Monkeyc compiler gives “invalid key format.” What’s the correct format?

Answer:

openssl genrsa -out temp_key.pem 4096

openssl pkcs8 -topk8 -inform PEM -outform DER -in temp_key.pem -out dev_key.der -nocrypt

What would’ve taken an afternoon of documentation digging was done in minutes.

Phase 2: The UX Shift

My first version was overloaded with labels, boxes, and numbers — fine for testing, but useless at a glance. I needed simplicity.

Prompt:

Redesign with a large EAT/STOP indicator and minimal calorie display. Prioritize instant visual feedback.

The AI suggested:

- A massive header taking 45% of the screen

- Bold text for EAT/STOP

- Simple “consumed – remaining” display

- Color logic: green for EAT, red for STOP

That redesign was the moment it felt like a product, not a prototype.

Phase 3: Persistence and Polish

Then came the first real bug: settings wouldn’t save between restarts. Calorie targets vanished. Reset times didn’t work.

Debugging prompt:

Daily target isn’t saving. Refactor to use Application.Storage and add reset time editing like TargetInputView.

Fixes included:

- Rebuilt storage using Application.Storage.setValue()

- Added full TimeInputView

- Validated input ranges (500–5000 calories)

- Added persistence tests that passed first try

It now remembered everything, even after a reboot.

What AI Got Right (and What I Learned)

1. Start Broad, Then Narrow

Begin with the roadmap, not the feature. It defines your scope.

2. Be Clear With Constraints

Specific numbers and formats save hours of rework.

3. Reference Patterns

Pointing to existing code or patterns keeps consistency.

4. Ask for Tests

Every major function came with automated tests, just by asking.

5. UX First, Always

A single “simplify this” prompt made the app usable.

Using AI Like a Teammate

In a few hours, I went from zero Garmin experience to a working, wrist-ready app.

Core Features:

- Real-time EAT/STOP indicator

- Button-based calorie entry (50-calorie steps)

- Custom daily target with persistent storage

- Midnight reset and timezone awareness

Technical Quality:

- Clean structure

- Passing tests

- Battery-efficient

AI handled setup, syntax, and scaffolding. I handled decisions, debugging, and polish. Together, we built something functional — and fun — in record time.

Conclusion

I went from a passing thought – wouldn’t it be cool if someone built this? – to actually building it myself in just a few hours. What started as curiosity became a working Garmin app on my wrist.